Nuances in Clean Architecture

In which I try to untangle the differences in Clean Architecture implementations.

Clean Architecture has seen some popularity as an approach to architecting complex code bases but inevitably has been interpreted in many and often conflicting ways. I wanted to get my head around this particularly as I've been refreshing my Java recently and have come across a number of differences in Clean Architecture implementations. This article is my attempt to list a number of differences I've spotted in the wild.

These differences aren't in any particular order and certainly aren't numbered. What? Did you think this was a listicle?

Presenters versus returned values

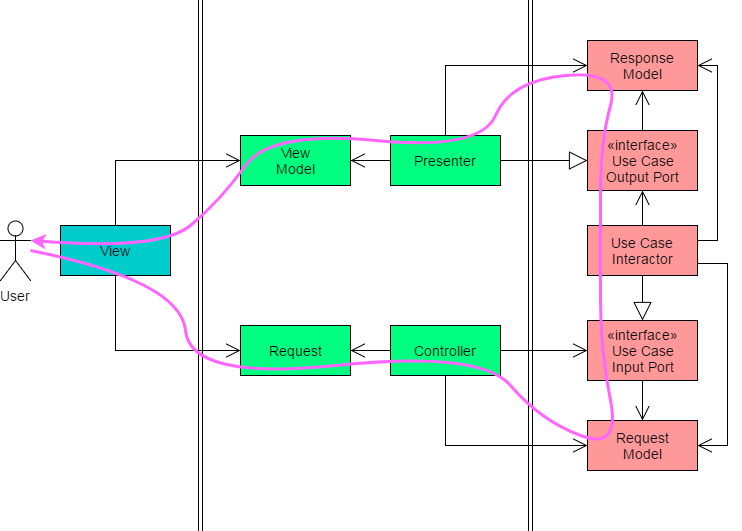

So if you learned Clean Architecture from it's creator then you will likely be familiar with the idea of presenters in the overall control flow. The idea being while a framework controller will construct a use case request model to inject into a use case, it does not receive the use case response model at all. Instead, a presenter already injected into the use case is given a response model, at a time the use case determines.

In this directors-cut interpretation of Clean Architecture, the controller is ignorant of the shape of a response model and is never tempted to even peak into it. The controller simply makes a request and then takes it easy.

When researching this I came across a brilliant question and response on StackExchange that summarises the "official" stance on why injected presenters should be used over returning response model.

In response to the question author's suggestion that it's more favourable for the controller to marry the use case and a presenter, rather than the use case knowing about the presenter directly, the responder quickly asserts:

That's certainly not Clean, Onion, or Hexagonal Architecture.

I like the passion for defending a canonical interpretation but I'm not really sure how it's helpful to someone trying to make sense of it all.

The responder then goes onto suggesting one should read up on the Dependency Inversion Principle and Command Query Responsibility Segregation without offering any real explanation of their importance.

The problem here is now whatever knows how to ask for the data has to also be the thing that accepts the data.

And why is that a problem I asked myself?

Yes! Telling, not asking, will help keep this object oriented rather than procedural.

And why is OO better than procedural?

The point of making sure the inner layers don't know about the outer layers is that we can remove, replace, or refactor the outer layers confident that doing so wont break anything in the inner layers. What they don't know about won't hurt them. If we can do that we can change the outer ones to whatever we want.

This made the most sense to me, "what they don't know about won't hurt them". I suppose the argument is the controller only cares about firing off the request and never handles the response, it does one job and is therefore simpler and easier to maintain.

My introduction to Clean Architecture was not from reading a book or an "official" blog post. A colleague of mine ran a showcase and later coached me on their interpretation. This interpretation completely missed the idea of presenters altogether, or at least if they did talk about presenters, I didn't retain that information.

It seems many others have also overlooked this detail, blissfully unaware of the unorthodoxy of their approach. I suppose "what they don't know about won't hurt them" too?

In a C# introduction of Clean Architecture the author happily introduces their readers to the concept of a use case receiving a request and returning a response. What filth. Their example also included a presenter, however it was quite separate from the use case, they passed the response from the use case into the presenter within the console runner. Scandal!

To be honest, going back to the StackExchange response on this topic, I like the summary at the end of the lengthy answer:

Anything that works is viable. But I wouldn't say that the second option you presented faithfully follows Clean Architecture. It might be something that works. But it's not what Clean Architecture asks for.

What works, works, right?

Use of request and response models

Request and response models are the layers of abstraction that separate your business logic from the outside world. They translate a request from a delivery mechanism or framework into language a use case understands and then a response is constructed and interpreted by a presentation layer. At no point, is a domain entity exposed.

I asked myself a question early on in my exposure to Clean Architecture. If my response looks like my domain entity why am I mapping the domain into a response? It's unnecessary complexity and indirection right? I'm not the only one, a questioner on StackOverflow asked why could the domain entity not be used as the request? Clever, I like the way your brain works internet person!

Sadly, enforcers of the one true clean way responded crushing the questioners spirit and mine in one fell swoop suggesting Clean Architecture could never be so fragile:

How could Clean Architecture possibly force rigidity and fragility? Defining an architecture is all about: how to take care widely of fundamental OOP principles such as SOLID and others…

Aight. You're entitled to strongly held beliefs I suppose. The responder then bashes more wikipedia links on the question authors head, this time to the Law of Demeter. Enforcers sure do like to call upon theory.

Luckily, we weren't the only ones. A recent article introducing an approach to Clean Architecture for Java 11 described use cases directly returning domain objects.

What do I really think? By doing this you are certainly introducing fragility to your code base if you let your use cases expose domain entities to the wider world. Is that a problem? It depends on your context. I suppose it also depends on your willingness and discipline to add new layers of indirection when your application calls for it.

I can certainly see an argument for just following the rulebook, it's simpler to teach and simpler to be consistent. That said, it's clearly a tradeoff for simpler contexts.

Use of the command pattern

The command pattern states that you expose a method that does stuff. Usually you will find the method called execute(), exec() or run(). This means that you can describe your application in a series of commands, all of which are called in the same way but each doing something different under the hood.

You can see why the command pattern translates quite well to the use case pattern, particularly if you're making sure your use cases do one thing.

That said, I've found no orthodox view on the use of the command pattern. In fact I've found a good mix of examples where use cases do more than one thing.

In the Slalom post previously mentioned, the example has multiple public methods in the FindUser use case, both findById() and findAllUsers() rather than a single execute().

In another example, this time in golang, I found the use cases provided a number of public methods that interact on the concept of a user object. For me, this means you end up defining use cases around nouns rather than verbs, which means they can end up doing too much. The issue with use cases doing too much is that they are harder to maintain because they are harder to understand. It also means that your directory of use cases no longer describe the things a user can do with the application, which for me was one of the selling points of Clean Architecture over MVC.

You certainly do find the command pattern in use for use cases though. The C# article uses a Response Handle(Request) method.

At Made Tech we certainly recommend the command pattern and you can see it in use in many of our public sector work streams.

I like the idea of a use case being linked to a single action. I like the way it forces you to decompose your application into small enough chunks and your directory structure describes what your application does. Your mileage may vary however.

Directory structure and packages

Talking of directory structures there are many interpretations and also how far you go to separate your delivery mechanism or framework from your domain and use cases.

The pattern we most often use at Made Tech is making sure we have separated our Clean Architecture code from our delivery mechanism. A common case for us is making sure Rails and our Clean Architecture are separated by keeping our Rails code in app/ and our use cases, domains and gateways in lib/. The GovWifi project is a clear example of this.

I've noticed elsewhere, particularly in languages that like to structure code as packages like Java and C#, you find domain, use cases, adapters and frameworks all in separate packages. The Slalom post certainly favoured this approach.

You then find everything in between. I can see the advantage of using enforceable package boundaries particularly with tools like Jigsaw in Java that allow you to keep implementation details hidden from the various layers of your application. This is much harder in Ruby and other dynamic languages where you have a vague idea of namespacing but everything ultimately runs in a global space. At this point the directory structure is your only defence which is why you see the separation of code into app/ and lib/ in Rails applications.

The naming of things

As I've been writing this article I've noticed all kinds of interchangeable language. Instead of discussing the naming of things, as the old adage suggests its one of our hardest problems as coders, I'll provide a few lists of synonyms instead and I'll let you interpret them as you will.

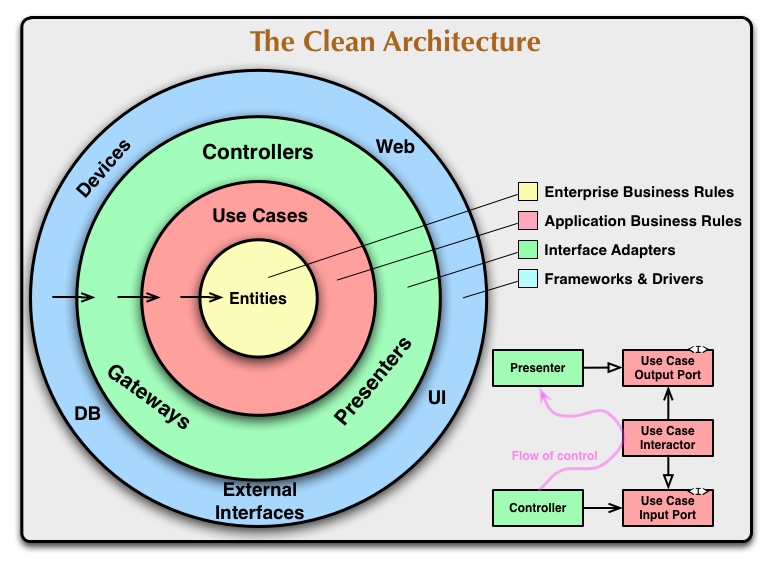

Frameworks and drivers

Frameworks and drivers represent the outside world. They are the outer layer.

Types of frameworks and drivers: Delivery Mechanism, Framework, Database, UI, Web, Program, Console Runner

Interface Adapters

The implementation detail of connecting your business rules with the outside world.

Types of Interface Adapters: Gateways, Repositories, Presenters, Controllers

Application Business Rules

The code that describes what your application does.

Types of Application Business Rules: Use Cases, Interactors, Actions

This layer also provides Ports, also know as Input/Ouputs Ports or Request/Response Models. These are the inputs and outputs of use cases.

Enterprise Business Rules

The code that represents the nouns of your organisation.

Types of Enterprise Business Rules: Entities, Domains, Models, Records

What to make of these nuances?

I'm not sure what to make of it all. Clearly there are different strokes for different folks. People will interpret however they will. The best way you can equip yourself for such a non-uniform universe is to understand the variations in the use of Clean Architecture and begin to reason when certain approaches may work over others.

You'll never 100% get it. People will disagree with you. That's okay, haters gonna hate. Just make sure you are empathetic to others and be open minded.

Sign up for new content weekly